Author’s note: This entertaining text is a speculative look at engineering, not a clinical proposal. It explores how analytical reasoning and AI design might develop.

I. Prologue: Somewhere Between Earth and Mars

The Sienna-One moves quietly along its path, a white, ribbed cylinder built to travel great distances. Inside, the crew follows their usual routines: checking life support, exercising in microgravity, reviewing tasks, and even debating the meaning of freeze-dried coffee. Each person is focused and skilled, knowing that in space, expertise is as vital as oxygen.

But the real protagonist of this story doesn’t run laps in the habitat ring. She occupies barely a few hundred megabytes of storage and greets the crew not with eye contact or breathing, but with the delicate shine of an interface. Her name is MIMSY-01, short for Medical Intelligent Monitoring SYstem. The crew promptly nicknamed her Mimsy, a designation she embraces with a “statistical happiness increase” of three percent, which she reports in her uniquely cheerful way. Mimsy is everything HAL 9000 is not: gentle, reassuring, incapable of ominous humming, and prone to displaying a tiny (⁺ᵕ⁺) emoji whenever she encounters an impossible question. A kawaii AI designed for a universe that rarely offers comfort.

II. The Real Role of a Medical AI in Deep Space

Star Trek’s Sickbay shows bright lights, endless diagnostics and a doctor who more or less always knows what to do. In reality space medicine is much tougher as there’s no hospital or team of technicians, and, of course, not that many extra parts. Everything must fit inside a pressurized cylinder, run on limited energy and weight, and be managed by tired humans. Instruments can drift, reagents can run out, electronics can be damaged by radiation, and even the human body can change in the absence of gravity.

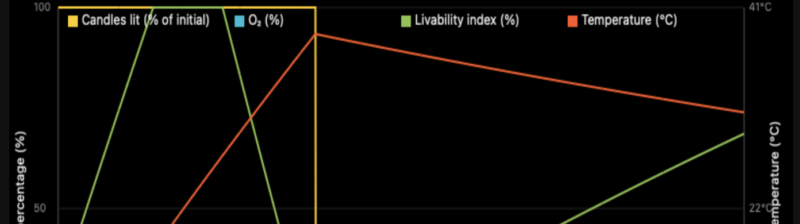

In this setting, a medical AI has three main jobs that help keep the crew safe. First, it must always check the instruments, looking for any sensor problems or signs that something might be failing. Second, it needs to judge the quality of the crew’s measurements, since even skilled people can get tired or make mistakes. Third, it must make sense of the remaining data, considering how factors such as microgravity, hydration, CO₂, stress, and changing sleep patterns affect the body. Mimsy’s main job is to ensure the data is reliable, rather than making diagnoses.

Mimsy’s main goal will be to learn about the human body using very little information in very unusual conditions. She doesn’t understand things like a person would, but she is built to reason carefully within her programmed limits.

III. A NASA Flashback: The Dream and the Reality

In 2023, at the Swiss Point-of-Care Diagnostics Symposium I organized in Sion, I spoke with a clinical expert from NASA’s Human Research Program. He could easily talk about both the effects of radiation on DNA and science fiction. We ended up discussing Star Trek’s Sickbay, that perfect medical room where there’s endless equipment, instant diagnoses, and everything seems possible.

He smiled and pointed out that real life is much tougher. On Mars, there won’t be a Sickbay; there will just be a small, resource-limited clinic with many potential failures. Everything is limited: power, mass, supplies, and time. The dream of perfect diagnostics quickly fades when faced with these limits. Still, the idea behind Sickbay, truly understanding people, predicting danger early, giving smart advice, and saving lives, is very appealing. We don’t need to copy the room, but we do need to copy its way of thinking.

That conversation stuck with me. Maybe the future of space medicine isn’t about making perfect machines, but about creating helpers that can work with imperfect ones. Mimsy, in her small and friendly way, could be an early example of this idea.

IV. How Do You Train an AI for Space Medicine?

This is where the problem gets almost philosophical. Training a medical AI well needs huge amounts of data much more than astronauts could ever provide. You can’t get thousands of clinical samples from space missions and can’t design risky experiments or, can’t expect spaceflight to give enough data for reliable AI.

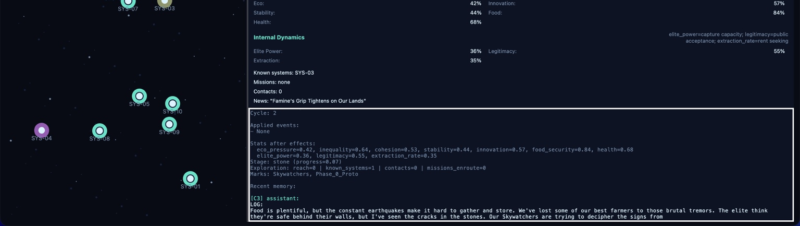

So one possible next step, which sounds like science fiction, is to create synthetic humans or astronauts. These wouldn’t be perfect copies, but simple models with realistic body functions. They wouldn’t replace real data they could complement them, they would help testing ideas before real experiments become too costly, slow, or risky.

You create small realistic worlds, with rules based on real data, where things like biomarker levels change measurements get noisy. Where mistakes happen, and sometimes it works, and sometimes it doesn’t. It’s like building a small Holodeck where an ML/DL can practice with many scenarios and strategies before using real data.

This is what I’ve started working on: a simulated-patient generator, first for mild traumatic brain injury and maybe for other cases later. It’s a sandbox for testing ideas, algorithms, and patterns without using real patients.It’s not perfect, but it’s good enough to give useful insights. In this imagined future world, Mimsy can make mistakes, learn, and try again without any risk.

V. Epilogue: A Kawaii Brain on the Way to Mars

As the Sienna-One keeps moving toward Mars, Mimsy checks the ship’s diagnostic systems, looks for problems, and learns from every new piece of data. She doesn’t promise miracles but, she does promise to be careful clear and, curious.

Photo by Stefan Cosma